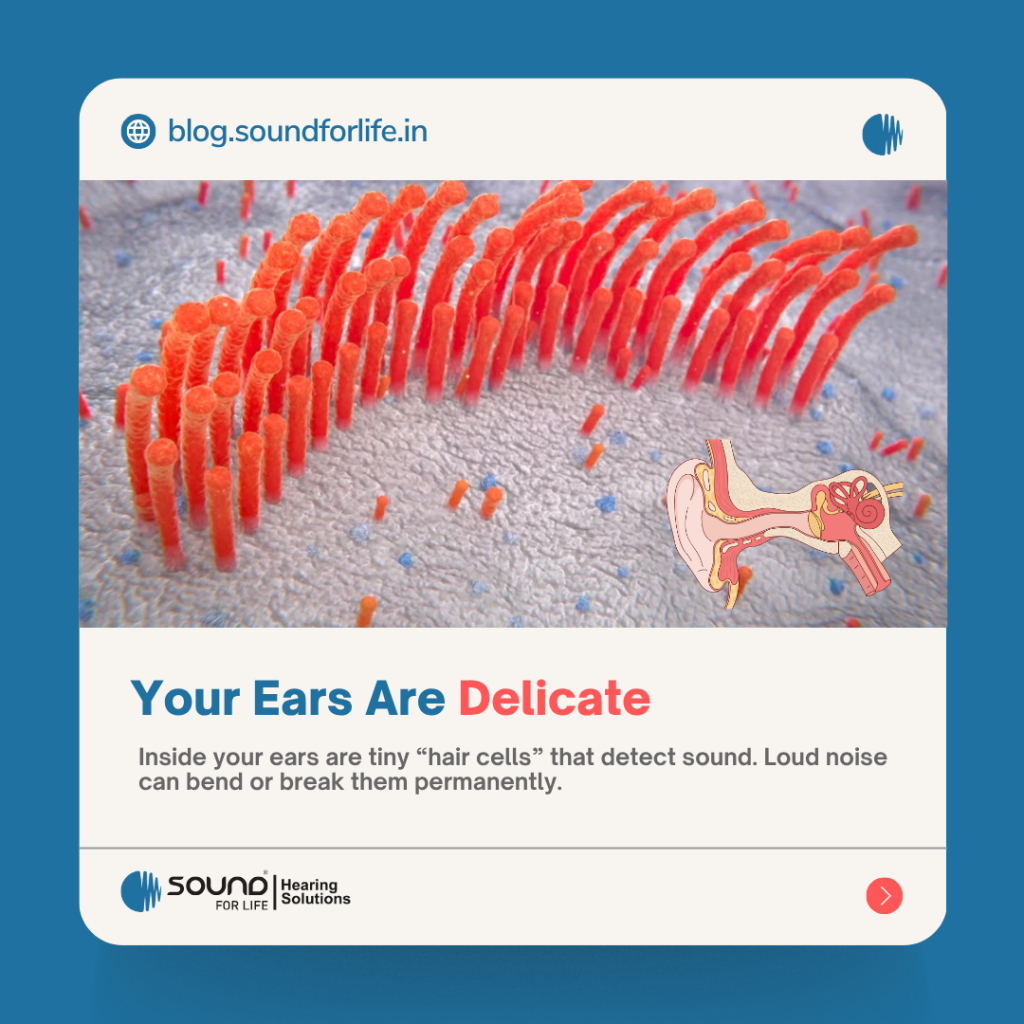

Our ears are delicate instruments. Inside each ear is a tiny spiral called the cochlea, lined with thousands of microscopic “hair cells” that sense sound. Very loud noises can bend or break those hair cells, causing hearing damage. This damage is called noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL). It can happen instantly (for example, from a sudden explosion or gunshot) or gradually over time if you’re exposed to loud noise day after day. Many people don’t notice the damage at first, they might only realize something is wrong when soft sounds become hard to hear or they start to hear ringing (tinnitus) in their ears after loud events. In fact, tens of millions of individuals already have some hearing damage from noise exposure. The good news is noise-induced hearing loss is preventable if we take the right precautions.

How Loud Is Loud? Understanding Decibels (dB)

Sound intensity is measured in decibels (dB). The decibel scale is logarithmic, which means each jump of 10 dB is a tenfold increase in sound intensity (about twice as loud to our ears). For example, a soft whisper is around 30 dB, a normal conversation is about 60–70 dB, and everyday home appliances like vacuums or hair dryers are around 70–90 dB. Once noise levels reach about 85 dB, even long exposures can start to harm your hearing. Above 100 dB, the allowable exposure time drops to minutes. Extremely loud noises (fireworks, gunshots, jet engines) can be 140 dB or more and these can cause pain and immediate damage.

| Sound (example) | Approx. Level (dB) |

| Quiet library or soft whisper Normal conversation Busy city traffic (inside car) Vacuum cleaner / hair dryer Lawnmower / power tools Motorcycle / sporting event Concerts / nightclubs Sirens / loud alarms Fireworks / gunshots | ~30–40 dB ~60–70 dB ~80–85 dB ~70–90 dB ~85–100 dB ~95–100 dB ~100–120 dB ~110–130 dB ~140–160 dB |

(These are approximate levels. Actual noise can vary – for example, rock concerts often exceed 110 dB, and standing near a jet engine or fireworks can reach 120–150 dB.)

There are some rules of thumb: if you have to raise your voice or shout to be heard by someone a few feet away, the noise level is likely over 85 dB and could be harmful over time. Common examples at about 85–95 dB include busy city traffic, motorcycles, lawn mowers, chainsaws, and power tools. If you’re at a concert, sporting event, or club, noise can easily reach 100 dB or more, even a few minutes at these levels can start to do damage. Sounds above ~120 dB (like sirens or fireworks) are extremely loud: they can cause pain and immediate harm and should be avoided or approached with strong hearing protection.

When Does Sound Become Dangerous?

Medical experts agree that noise above about 85 dB is in the “danger zone.” According to studies, 85 dBA (an A-weighted measure focusing on human hearing) is the threshold where an 8-hour workday of exposure starts putting hearing at risk. Above that level, the safe listening time drops rapidly. In fact, for every 3 dB increase above 85 dB, the maximum safe exposure time is cut in half.

For example:

● At 85 dB, the safe daily exposure is about 8 hours (an average workday).

● At 88 dB, the safe time is roughly 4 hours.

● At 91 dB, only 2 hours are safe.

● At 94 dB, about 1 hour.

● At 100 dB, only about 15 minutes without protection.

These figures are general guidelines; individual susceptibility varies. But the key takeaway is that louder sounds require much shorter exposure. The World Health Organization notes that safe listening time plummets as volume rises: you could listen up to 40 hours a week at 80 dB, but only about 4 hours a week at 90 dB without risk. (Notice how just a 10 dB increase from 80 to 90 dB cuts safe time by tenfold.)

| Sound Level (dB) | Max Safe Exposure (per day) |

| ≤ 70 dB 85 dB 88 dB 91 dB 94 dB 100 dB | Indefinite – normal conversation and most home noises ~ 8 hours ~ 4 hours ~ 2 hours ~ 1 hour (approx.) ~ 15 minutes |

(Remember: If you’re exposed to noises above these levels, either shorten the time or use hearing protection. OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) and health agencies warn that noises above 85 dB are hazardous without protection.)

Everyday Noisy Situations to Watch

At Home and Everyday Life:

Some of the loudest noises happen right at home or in our neighborhoods. Lawn mowers, leaf blowers, and power tools can hit 90–100 dB, which means even a short yardwork session without earplugs could start to harm your hearing. Vacuum cleaners, blenders, and hair dryers often range 70–90 dB – still loud if you use them for hours. And children’s toys can be surprisingly loud: a study by the Mayo Clinic found some toys produce 90 dB or more, especially when held close to the ear, and can even reach 120 dB in extreme cases. The rule for kids’ toys is simple: if a toy seems very loud to an adult, it’s too loud for a child. Always test toys at ear level and turn them down if needed.

Workplaces and Workshops:

Many professions involve noise risks. Construction sites, factories, farms, and even busy cafes or garages can be loud. For example, printing presses, factory machinery, and heavy equipment often reach 85–95 dB. Forklifts, bulldozers, jackhammers, and ambulance sirens can be 95–110 dB or higher. If you work around these noises, employers are supposed to provide a “hearing conservation” program once levels hit 85 dB or more. Always use earplugs or earmuffs on loud jobs, and take breaks in quiet areas. Even office workers aren’t completely safe: if you have to shout over the noise at your workplace, it’s probably too loud.

Music, Concerts, and Headphones:

Loud music is a major source of hearing damage for many people, especially teens and young adults. A rock concert, nightclub, or festival often blasts sound at 100–120 dB. Standing near loudspeakers or drums just for a few minutes can strain your ears. In headphones or earbuds, volumes can easily reach 100 dB or more. Safe listening practices say: keep your device volume at no more than about 50–60% of maximum, and try not to listen to very loud music all day. In fact, the WHO and audiologists recommend staying below about 80 dB on headphones and taking regular breaks. A handy tip: if someone nearby can hear your music while it’s playing, it’s too loud.

Other Situations:

Loud movies, sporting events, even household items like fire alarms, sirens, and some fireworks are risky. A car horn close by is around 110 dB. Fireworks and gunshots can reach 140–160 dB – levels that can cause immediate damage. Even something like a motorcycle revving or a subway train passing can be well over 95 dB. Remember, it’s not just intensity but also duration. An instant of loud noise (like a balloon pop) usually causes only a tiny burst of damage, but standing near a noisy sports arena for 2 hours could do the same damage as a very loud burst. Always use hearing protection in any of these situations.

Signs of Hearing Trouble

Your body often warns you when sounds are too loud. Ringing or buzzing (tinnitus) after a loud concert is a red flag. If sounds seem muffled or “far away” after you’ve been in noise, or if you find yourself turning up the TV or phone volume higher than before, your ears may have suffered temporary (or permanent) damage. After a noisy day, needing a moment of silence for your ears to “recover” is a sign. According to experts, if you leave a place with ringing ears or trouble hearing conversation, you’ve just been overexposed to noise. Early detection is key, if symptoms persist, talk to an audiologist. Even a little hearing loss can creep up gradually, first affecting high-pitched sounds (like birdsong or beeping devices) before you notice it in speech.

Long-Term Effects: Hearing Loss and Tinnitus

Repeated exposure to loud sounds can eventually kill off so many hair cells that permanent hearing loss sets in. Unlike a cut that heals, hair cell damage cannot be reversed. Over time, NIHL can make it hard to understand speech, especially in noisy places. About a million adults have some noise-related hearing loss, and a quarter of adults who think their hearing is “good” actually already have hidden damage. A common long-term effect is tinnitus, a persistent ringing, buzzing, or roaring in the ears, which affects quality of life and sleep. People with early hearing damage might withdraw from conversations, feel stressed, or have trouble at work or school. That’s why prevention is crucial: once hearing is gone, the only fix is expensive hearing aids or cochlear implants.

Protecting Your Hearing: Tips for Safe Listening

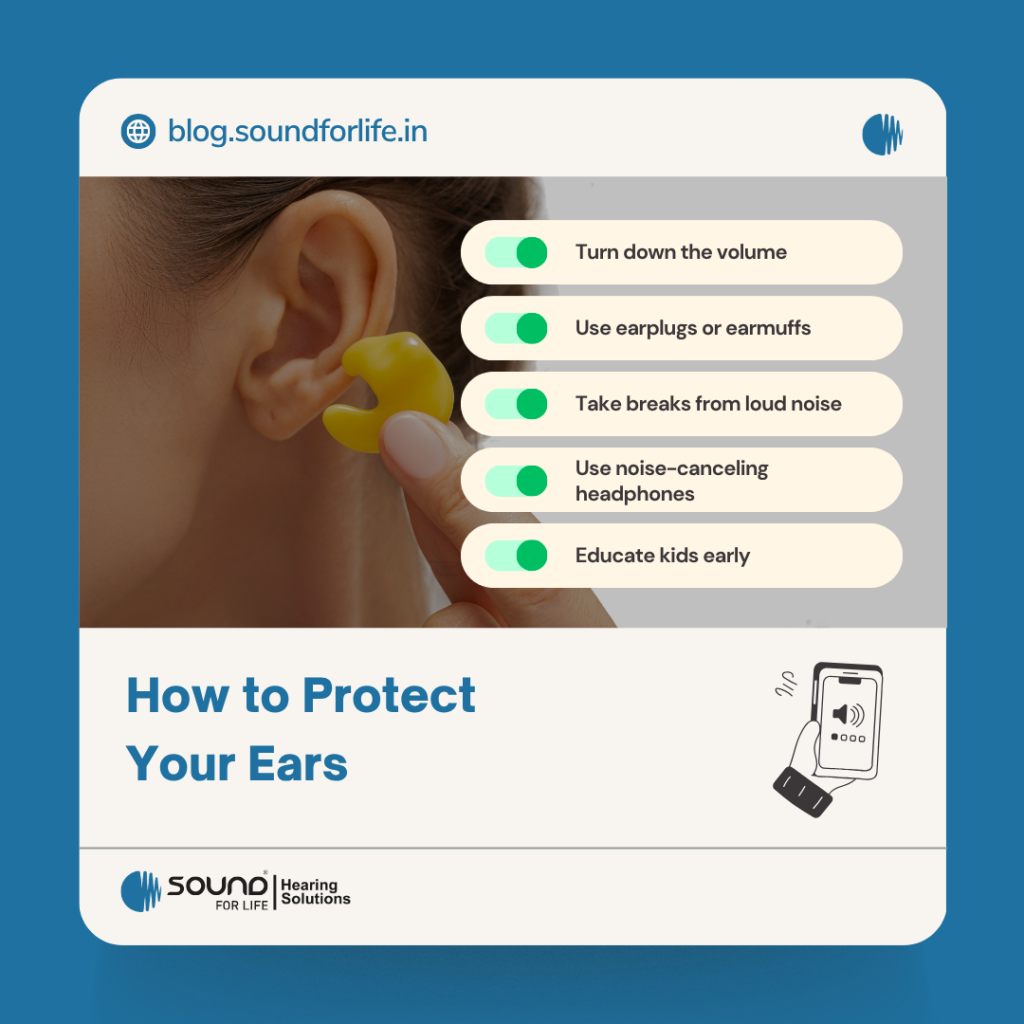

Preventing hearing loss means lowering volume, limiting time in loud sound, and using protection. Here are some practical tips:

● Turn down the volume

Keep music and media at a comfortable level. As WHO recommends, try setting devices to 60% of max volume or below, and use volume limiters if available. On speakers, don’t blast music; if you need to shout to talk to someone a few feet away, it’s too loud.

● Use ear protection

In noisy environments (concerts, power tools, engines), wear earplugs or earmuffs. High-fidelity (musician’s) earplugs are great for concerts as they lower volume evenly without muffling. Keep a pair of earplugs in your pocket: they’re cheap and easy to use.

● Choose noise-canceling headphones

They reduce background noise so you don’t have to raise volume. WHO suggests using well-fitted, noise-canceling headphones in quiet settings to avoid turning up the volume in noisy places.

● Limit exposure time

Take listening breaks. If you’re in a loud place, step outside for a few minutes to give your ears a rest. For workplace or machine noise, follow the “3 dB rule”: cut exposure time in half with every 3 dB increase over 85 dB. Even at home, don’t run a loud vacuum or lawnmower nonstop, pace the work and take breaks.

● Be aware of your surroundings

Move away from loudspeakers, engines, or machinery when possible. If you’re driving, avoid long periods with music on high; if sirens or honking blare, roll up windows.

● Check sound levels

Apps are available (like the CDC/NIOSH Sound Level Meter app) that turn your phone into a decibel meter. At concerts or parties, use them to gauge if noise is dangerously high. Remember WHO’s guidance: below 80 dB is generally safe for most of the day.

● Watch for warning signs

Ringing ears, muffled hearing, or needing higher volumes on your devices are red flags. These mean it’s time to back off the noise and protect your ears. Don’t ignore them, addressing the problem early (by seeing a specialist or changing your habits) can prevent permanent loss.

● Educate kids and teens

Children’s ears are still developing and can be even more vulnerable. Teach young people to limit headphone volume (sharing your phone “ear” trick or the “60/60 rule” – 60% volume for 60 minutes max), and to take breaks. If you can hear their music or game sounds from a distance, it’s too loud. When taking kids to events (parades, fireworks, sports), bring child-sized earplugs or earmuffs.

By practicing these safe listening habits, you give your ears the best chance to stay healthy for life. Hearing loss is gradual and often goes unnoticed until it’s serious, so it’s worth being proactive. Remember: once our hearing is gone, it’s gone, but it’s never too late to start protecting it.

Sources: Authoritative health agencies and audiology organizations provide these guidelines.